Dogs

When I look out of the window in my studio in Hamburg, my gaze falls on an urban dog park. If I didn’t have so much work to do, I could spend whole days watching the dogs jumping around and sniffing each other. At first, it was a piece of grass fenced off with chicken wire and with benches for the dog owners. Then so many dogs came, and they used the lawn so intensively that no grass has grown there for a long time. When it rains, the area dissolves into mud. In summer, the ground is often as hard as concrete. But the dogs don’t seem to mind. Plus, they have no choice.

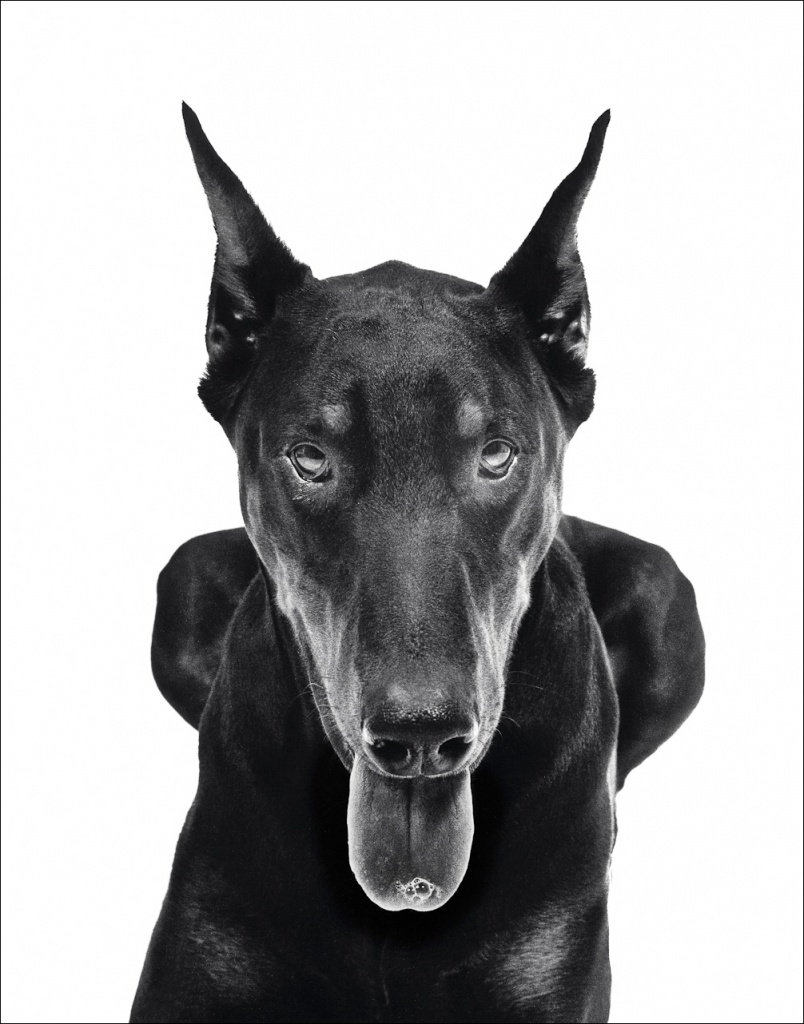

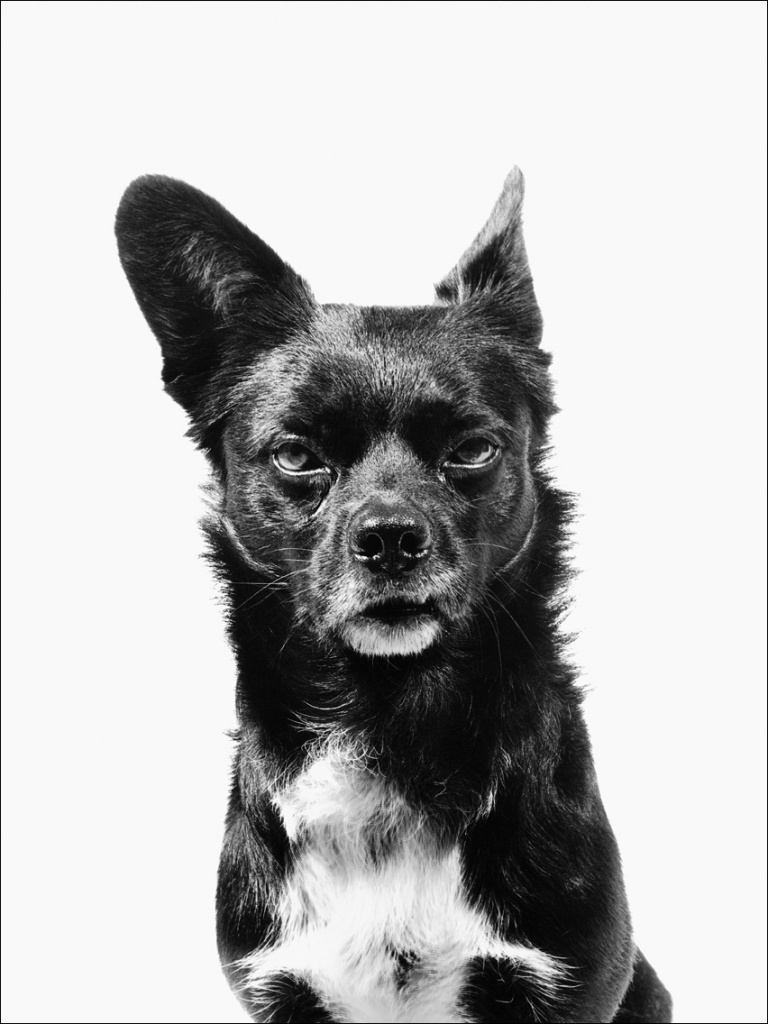

They are typical city dogs. There is hardly a big dog among them, most are tiny: pinschers, chihuahuas, pugs, dachshunds. They live in apartments, and when they’re outside, they’re not allowed to run without a leash. The sight of dogs like these, tied up, waiting outside a supermarket, makes my heart beat in sympathy. Sympathy with the prisoner. This penned-in-by-four-walls existence is emphatically not suitable for dogs.

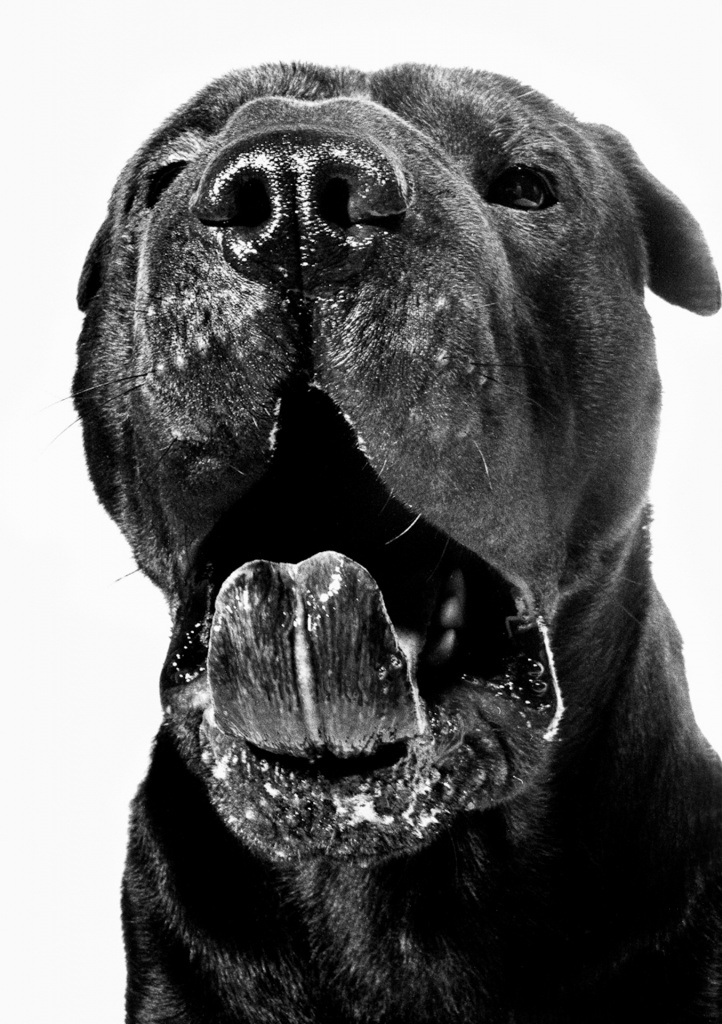

To be able to make at least a few leaps and bounds is an elementary need, even for lapdogs. I see how much spirit they have when they romp with each other in this limited space under my studio window and how they relish being able to move freely. Their sheer joy and eagerness when their humans throw sticks and balls for them knows no bounds. Then there are the attractive potential partners. As far as that goes, the dog park reminds me of a gigantic casting. Except that with dogs, it’s not the appearance that counts, but the smell.

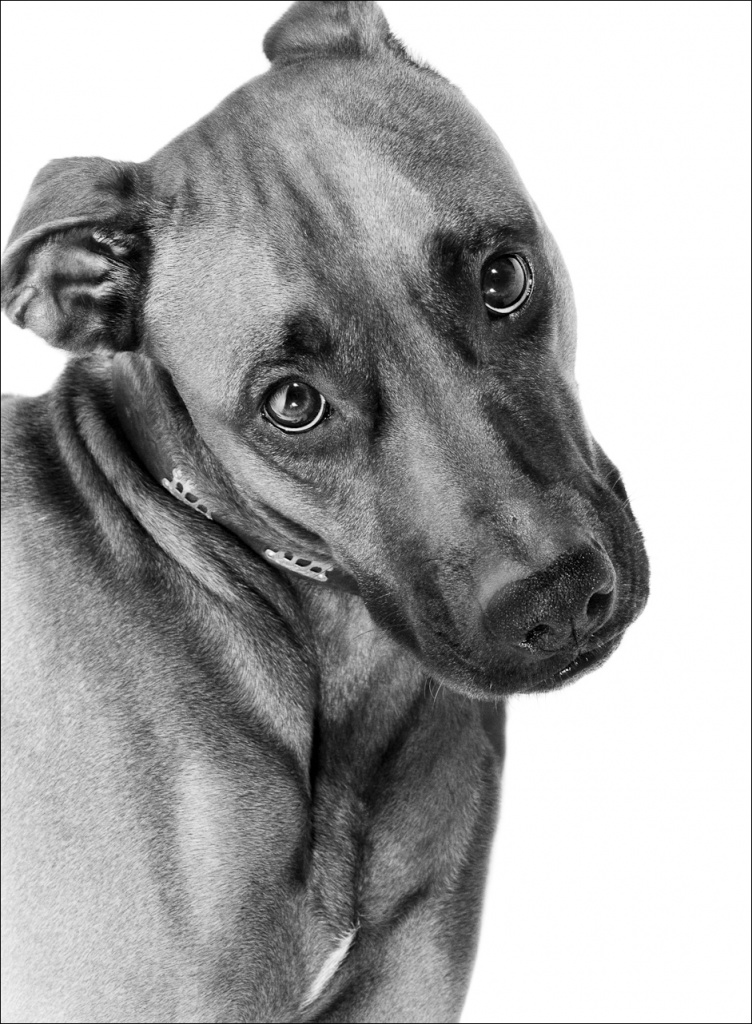

Until a few years ago, a small black mongrel lived in the photo studio opposite on the floor, a stray my neighbor had picked up on the street while on vacation in Spain. This dog was the perfect example of how contact with people makes the dog human. Chacho was intelligent and docile, and quickly became a typical lap dog. At the same time, he displayed dignity and an aloof personality, whose origin I suspected in his street past. I photographed him often. Although he was not one of the trained “photo dogs” I often worked with for publicity photos, he granted me a portrait session in the studio – a true vote of confidence.

By that time, we had developed a mutual ritual: Every morning, the dog waited outside my studio door. As soon as I opened it, he darted in and stood rooted to the spot in front of the refrigerator. He knew there was salami in there, especially for him. Every morning I cut off three small pieces, smaller than sugar cubes – I didn’t want him to get fat. I would hold up a cube of salami, and Chacho would roll over until I dropped the piece of sausage into his open mouth. We repeated this exactly three times, after which he took off. He knew it would have been useless to beg. And obviously he could count to three at least.

I don’t want a dog, because I know could never meet its needs. However, I grew up with dogs, cats and pigs, and had a close relationship with animals, closer than with many of the people around me. That came much later. I still feel a great affection for animals.

In my childhood, Blasso, our German shepherd, was my closest companion. My older brother had been given him as a puppy and was responsible for training him, but later had little time for the dog. Blasso had a job: his task was to guard our house. At night he was chained up. The dog had a strong sense of hierarchy. He was almost always fed by my father, who was the only person allowed to come near him while he was eating. Blasso accepted him as the alpha dog. My father never displayed any affection to the dog, and never stroked him. Blasso mainly got meat scraps from the horse butcher. But even that cost money, which my father had to earn laboriously by delivering heavy sacks of flour. From his point of view, the dog was yet another mouth to feed besides his six children.

I was the youngest, an introverted child. The whole world was my adversary. No one was allowed to touch me, not my mother, not my brothers and sisters. But I hugged and stroked Blasso the dog. Blasso and I were friends. I think the dog felt the same way. As a child, I was often in hospital for a long time. I had a bone disease and had to have several operations on my legs. When I returned home on crutches, it was always the dog who displayed the greatest joy at seeing me again.

And despite my deep affection, I did something that I am ashamed about I think about it today: I trained my friend. Time and time again I made him jump over a wall in our garden, which was too high for him. In retrospect, I would say I forced him to learn because I was looking for an outlet. I took out on the dog my anger at the whole authoritarian adult world, at the teachers, the Nazi era with its constraints and orders.

It was during my apprenticeship as a window dresser that someone poisoned Blasso. It must have been our neighbor, who was bothered by his barking at night when the moon was full. I dug a grave for my old friend in our backyard, I buried him and marked the spot with a cross.

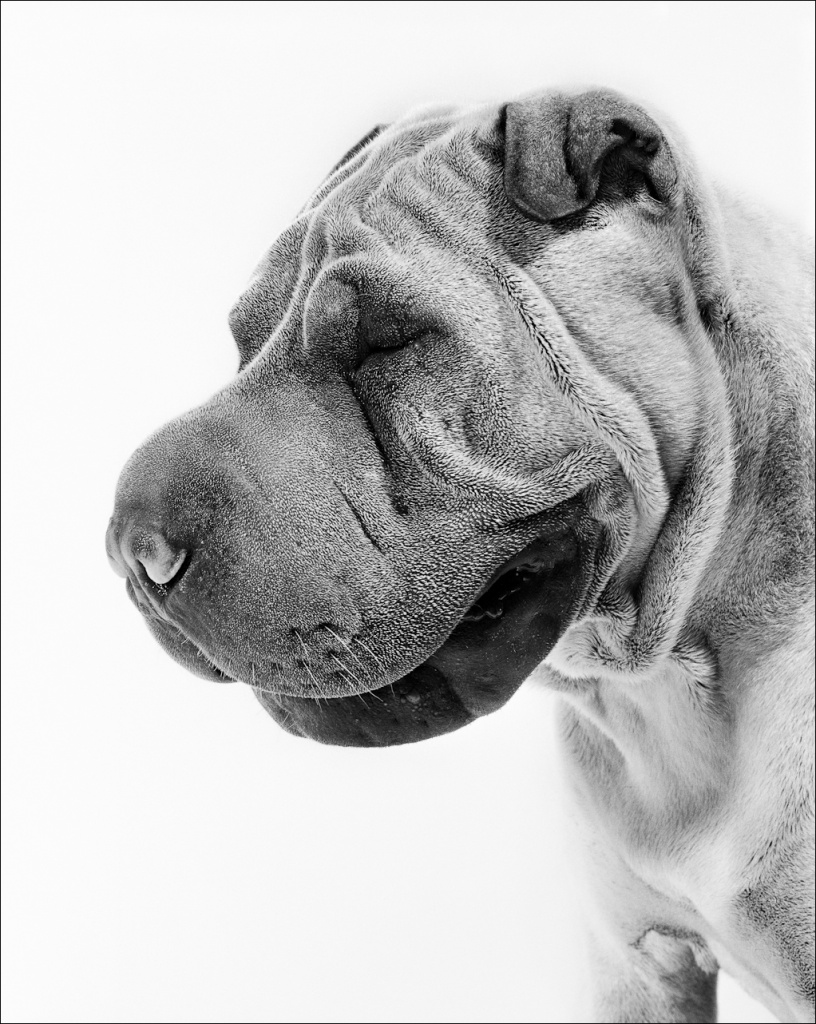

The solidarity I feel for dogs to this day is rooted in those experiences. A domestic cat still has the freedom to run around and catch mice. The wolf hunts for a sheep. For the dog this freedom is over. He is dependent on humans since he no longer has to look for his food independently. In exchange for this dependence, ideally he receives our affection.